Augmented reality technology may soon be the newest gadget available to crime scene investigators. A researcher at the Delft University of Technology is developing a system to allow police investigators to construct three-dimensional virtual models of crime scenes and support field agents with augmented reality information. Augmented reality (AR) is a relatively recent technology that integrates information and graphics into mediated representations of the built environment or natural world, blurring the line between the physical and the digital. Currently, it almost exclusively exists as a Smartphone novelty –see yelp’s “monocle” feature on their mobile app or the augmented reality browser Layar— but the technology may soon become more integrated into our daily lives through the use of AR-enhanced glasses. Most notably, Google seems to be making a move toward the creepy convenience of wearable computing. The New York Times recently reported that Google is developing glasses that “will have a low-resolution built-in camera that will be able to monitor the world in real time and overlay information about locations, surrounding buildings and friends who might be nearby….” Essentially, in the near future, we’ll all have Terminator vision. The Delft project aims to use the technology as more than a novelty, giving CSIs the capability to tag objects such as bullet holes or blood splatters in a virtual representation of the crime scene built from the data collected by investigators. It also allows the investigators to consult experts back at the precinct –or on the other side of the world– who, via a live video feed from a camera mounted on the glasses, see what the investigators in the field see. The system stores all the gathered evidence and information as part of the 3D model, which is itself admissible in court as evidence.

Detective Land stepped into the bathroom at the back of the apartment. Pink porcelain covered the walls, pink towels scattered along the pink tile floor, and in the empty pink bathtub a white body lay awkwardly. “What are we looking at, Quin?”

“Pink.”

Land raised an eyebrow at the medical examiner. “Very insightful. How about the body in the tub?”

“Rose Fishman. 41 years old. Strangled from behind with what looks like the belt of her bathrobe. I’m calling the time of death between 8pm and 10pm last night.”

“Murder? Robbery gone wrong?”

“No signs of forced entry.”

“What about that window? Was it open?”

“It was. Cleaning lady climbed up the fire escape to see what was blocking the bathroom door. She called it in. But she can’t remember if it was open or closed.”

“Cleaning lady. Well that explains why house is spotless. Most thieves and murderers don’t clean up after themselves.” Land turned to one of the uniforms on scene: “I’m going to need a full statement from her. And keep her at the station until I get back.”

Squatting down over the body, Quin continued offered his insight. “Bathroom looks like a war zone. And judging from the wounds, I’d say there was a bit of a struggle. Maybe our killer was looking for something?”

“We don’t even know if there was a killer yet. Something’s not right. Why the bathroom? Why today?” Land rubbed his eyes. “Alright,” he said, “let’s see what they can find back at the station. SPECS, everyone.” Land, Quinn, and the other investigators on scene all lowered the standard-issue field goggles onto their faces. Land sighed and, with a little reluctance, touched the small button near his temple. Three short beeps. Suddenly the clear lenses came alive. A new world revealed itself to the detectives with numbers, lines, estimated distances, floor plans, numbers, images, data. It was all data. Everything was being recorded, measured, searched, cross-referenced. All in a split second. It didn’t matter how often Land used the glasses, the impact of so much information at once always made him nauseous, though the younger detectives never seemed to have a problem with it. While the 3D model was constructing itself and uploading to the precinct database, Land starting planting his markers.

Crime is confronted by and pursued from its physical traces. But these traces, these vestiges of a transgressive moment, have a limited lifespan and can be accidentally corrupted by investigators in the field. With augmented reality crime scenes, however, that’s not the case. The technology allows pristine spaces to be digitally preserved indefinitely. But more than that, it makes it theoretically possible for the entire investigative process to be outsourced. Space is becoming as malleable and fluid as photographic images. We can know everything now. Everything from everywhere at anytime. The notion of the mysterious or the unknown is fast becoming a nostalgia. While the romantic may lament the loss of the unknown, the detective celebrates it, for it is his job to discover the unknown and reveal the latent messages encoded in space.

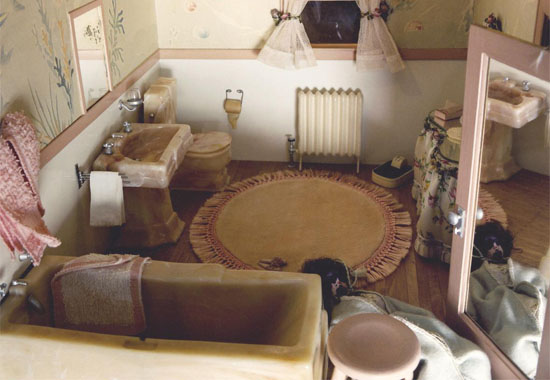

While certainly invaluable as field tools that optimize a police department’s resources, the information collected from augmented reality crime scenes will also make an incredible training tool for new investigators. Though AR is on the bleeding edge of forensic investigation technology, it shares a premise with a more archaic method developed in the early days of forensic science when reconstructed crime scenes, built at the the scale of a dollhouse, proved to be valuable training tools for the earliest investigators. These tiny models were created by millionaire heiress Frances Glessner Lee. She called them The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.

Witness report, March 31, 2022: “I entered her apartment and found it in order but the odor was very strong. The bathroom door was closed. I tried to open the door could only get it opened a little bit. The odor was much stronger around there. I immediately went downstairs and climbed the fire escape, entered the bathroom through the window and once inside, I found Mrs. Fishman dead. I can’t remember if the window was opened or closed.”

Glessner Lee, who grew up in the fortress-like Glessner House in Chicago, had an unusual hobby for an early twentieth century society dame. Using police reports and witness statements, she constructed composite models of crime scenes at the scale of one inch to one foot. Matronly Glessner Lee –who some speculate was the inspiration behind Angela Lansbury’s character in Murder She Wrote— was passionate about police work and believed in the need to improve training for those investigating violent deaths. She also believed through careful observation and evaluation of a space, indirect evidence will reveal what transpired within that space. Her models present uncorrupted crime scenes generated from evidence, extrapolation, and Glessner Lee’s own penchant for interior design. Architect and educator Laura J. Miller writes about The Nutshell Studies in her essay “Denatured Domesticity: An account of femininity and physiognomy in the interiors of Frances Glessner Lee.” She describes how Glessner Lee subverted the notions of domesticity typically enforced upon a woman of her standing by using the skills she learned as a young woman to educate and entertain police detectives instead of debutants or tycoons. But the Nutshells are more than useful tools for the study of forensic investigation. Miller writes that Glessner Lee’s dioramas “peel back the domestic scene’s veneer of privacy, propriety, and routine, opening the home to reinterpretation through its exposure as the scene of a crime.” Though the essay focuses on the domestic interior, such observations ring true for any architectural space. Her descriptions of domestic space as a conflict between cultural scripting and natural behavior reveal an implicit, though rarely discussed facet of architecture: it’s naive optimism. Or perhaps egotistical expectation. That is to say, the notion that a space will be used as intended by its architect. Programmed space constructs behaviors. The criminal act violates those constructions, revealing them to be fictions. From this initial transgression, the investigator constructs his own fictions – speculative narratives to explain the crime and locate the criminal.

In approaching the space from an objective perspective, the detective sees architectural space more purely than the resident, and perhaps he even comes to understand its use and affordances in ways unanticipated by the architect. “The forensic investigator,” Miller writes, “takes on the tedious task of sorting through the detritus of domestic life gone awry….the investigator claims a specific identity and an agenda: to interrogate a space and its objects through meticulous visual analysis.” There are specific methods –geometric search patterns or zones, for example– by which the forensic investigator completes his analysis of a space. There’s an elegant logic to these methods, as they were have been refined over more than a century to ensure complete coverage and to maximize resources. But if the augmented reality future ever comes to pass, these methods will have to be completely rethought. The aesthetics of search will be redesigned around virtual representations of space. It’s not difficult to imagine a future where a preserved crime scenes is something like a reconstructed photosynth, built from the assembled images and data gathered by multiple officers and investigators, each with their own unique objectives and predispositions. Whereas the painstakingly crafted Nutshell models reveal Glessner Lee’s own biases and beliefs, such AR composite models are near-instantaneous, collective representations that make the detective’s “meticulous visual analysis” a desk job.

Both Glessner Lee’s models and the AR crime scenes present a subversive view of architectural space. With these models, be they physical or virtual, representation functions not just as illustration, but as revelation. In “Denatured Domesticity,” Miller writes that “The diorama’s removal of one wall of a room emphasizes the absence of a critical mediating boundary and destabilizes conventional understandings of interior and exterior, and therefore, the coding of private and public space.” The space of a crime scene is defamiliarized by the view afforded by the removal of this wall. A virtual model essentially removes all walls, exploding the crime scene to be reassembled at the investigator’s will. By now it’s largely accepted that new media technologies denigrate, if not completely eradicate, the boundaries between the interior and the exterior of our everyday lives; a process that continues with each new device and piece of software. As the walls surrounding our own environment collapse and our lives are opened to new investigations, I’m reminded of the words of German philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin. In his essay “A Little History of Photography” Benjamin writes, “But isn’t every square inch of our cities a crime scene? Every passer-by a culprit?”

As for the Pink Bathroom…

By the time Field got back to the station, the SPEC technicians had ruled the death a suicide. Mrs. Fishman used the stool to hang herself from the bathroom door. Small threads were found hanging from the door that matched the fibers found in the wound around her neck. So that was it. Sure, it took some of the romance out of the job. And yeah, it sometimes made him feel obsolete. But it was worth it if it meant more lives were saved.

[Note: Though the date has been altered, the Witness report and the original image of Glessner Lee’s model of The Pink Bathroom were excerpted from The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death]