“One of the essential characteristics of the bunker is that it is one of the rare modern monolithic architectures.” So writes philosopher-artist-dromologist Paul Virilio in his exegesis of World War II defensive fortifications, Bunker Archeology. These poured-in-place pillboxes aren’t just modern, they’re modern concentrate—efficiently constructed for a single purpose and devoid of any style or ornament because, as Virilio writes, “the omnipotence of arms volatilized what was left of aesthetic will.” If Le Corbusier’s houses are machines for living, the concrete bunker is a machine for surviving, designed to stand against bombs, bullets, gases, and flames. But in parts of the world where war is now a fading memory, bunkers linger on this earth without purpose, decaying, tied inextricably to the past, a haunting reminder of violence, a ghostmodern architecture.

Some of these underground bunkers were incredibly expansive, intended for long-term occupation, but many others were martial follies. Today, they’re half-buried along coastlines or looming silently and mysteriously in the middle of cities, too massive to be destroyed but often too difficult to be repurposed. Apparently, a side effect of being built to withstand mortar attacks is the ability to confound planners and developers—perhaps there’s a lesson there. Yet despite the difficulty of renovating a structure with a wall thickness measured in feet, some enterprising organizations and architects are doing just that, appropriating bunkers to imbue them with a new life and new meaning.

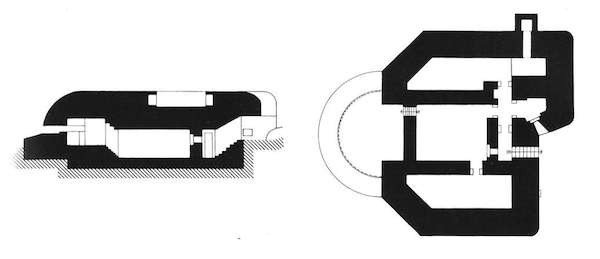

BIG’s Blåvand Bunkermuseum reconstructs the bunker’s original cannon out of glass “as a ghost or a reflection of the war machine it was meant to be.” For Virilio, the removal of a cannon “deconsecrates” a bunker. By that logic, BIG’s project re-consecrates the structure for a new denomination. The canon, once an instrument of ruination, is now an instrument of illumination, a skylight above an exhibition space. BIG describes its design as the “antithesis” to the existing structure: “vacuum rather than volume—transparency rather than gravity.” These are themes that recur in many of these projects.

Among architects, there seems to be renewed interest in Brutalism these days, and on purely aesthetic terms, it would be easy to think of these projects as examples of a New New Brutalism. After all, the Brutalist buildings of the 1950s and ‘60s were often derided as “bunkers,” although their raw concrete surfaces are more likely to harm their occupants than any invading military force. But like any good -ism, these projects represent both an aesthetic and an ethic. There’s actually a lightness to all these structures, an effort to mitigate the weight of the original bunker—and not just its literal weight. These bunkers carry a historic heaviness. They can be a psychological burden for people who don’t want to be reminded of the horror of war, but who are confronted by it every day, who literally live with it. While these renovations can’t erase the past, they can imbue its relics with new meaning.